|

Фатех Вергасов |

|

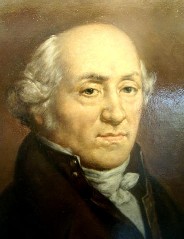

| Abraham-Louis Breguet | |

Abraham-Louis Breguet

никогда не был очень хорошим бизнесменом.

Он направлял свои усилия главным образом в сферу исследований и

повышения качества своей продукции и не гонялся за прибылью.

Именно по этой причине в начале 1791 года он отделился от своего

партнера Xavier Gide,

которой сосредоточился исключительно на

вопросах материалов.

Личный энтузиазм сердечность и

теплота помогли Брегету создать круг близких друзей, которые на

протяжении всей его карьеры помогали ему преодолевать многочисленные

трудности и невзгоды. Его обширная переписка показывает преданность его

друзей, выходцев из самых различных социальных слоев, в различных

жизненных ситуациях на протяжении многих лет

В самом начале его карьеры

аббат

Joseph-François Marie, его профессор математики и учитель

королевских детей, ввел его во французский двор, где он обзавелся

многими важными знакомствами и связями.

Во время Революции охранная

грамота, выданная его другом

Jean-Paul Marat,

позволила ему в августе 1793 года избежать ареста и

покинуть Францию.

Хотя его друг Dumergue

и убеждал его укрыться в Англии, Брегет в конце концов избрал родную

Швейцарию, где было много друзей, производителей часов.Samuel Roy,

Louis Decombaz и Jacques-Frédéric Houriet,

со временем, позднее стали его

основными корреспондентами по переписке в этой стране. Abraham-Louis Breguet

никогда не был очень хорошим бизнесменом.

Он направлял свои усилия главным образом в сферу исследований и

повышения качества своей продукции и не гонялся за прибылью.

Именно по этой причине в начале 1791 года он отделился от своего

партнера Xavier Gide,

которой сосредоточился исключительно на

вопросах материалов.

Личный энтузиазм сердечность и

теплота помогли Брегету создать круг близких друзей, которые на

протяжении всей его карьеры помогали ему преодолевать многочисленные

трудности и невзгоды. Его обширная переписка показывает преданность его

друзей, выходцев из самых различных социальных слоев, в различных

жизненных ситуациях на протяжении многих лет

В самом начале его карьеры

аббат

Joseph-François Marie, его профессор математики и учитель

королевских детей, ввел его во французский двор, где он обзавелся

многими важными знакомствами и связями.

Во время Революции охранная

грамота, выданная его другом

Jean-Paul Marat,

позволила ему в августе 1793 года избежать ареста и

покинуть Францию.

Хотя его друг Dumergue

и убеждал его укрыться в Англии, Брегет в конце концов избрал родную

Швейцарию, где было много друзей, производителей часов.Samuel Roy,

Louis Decombaz и Jacques-Frédéric Houriet,

со временем, позднее стали его

основными корреспондентами по переписке в этой стране.Брегет был весьма близок с John Arnold, известным английским производителем хронометров, и его сыном John Roger. Тем не менее, была ещё одна защита также и в Швейцарии - его бывший ученик Fatton помогал ему в делах. А ещё Dumergue, который присматривал за сыном Брегета в то время как последний стажировался в Ангилии в мастерских Arnold. 2 Представление Брегета Испанскому двору состоялось, благодаря Augustin de Betancourt, который к тому времени уже продал большое количество часов в Испании.Betancourt представил часовщика и мистеру Castaneda, котрый во время своего путешествия в Париж купил много часов для испанской королевской семьи и двораt. Благодаря привелегии знакомства с Maurice de Talleyrand, министром иностранных дел, Брегет имел возможность использовать дипломатическую почту для рассылки своих часов по Европе. Через Maurice de Talleyrand он также продал много часов принцу Don Ferdinando, будущему королю Испании, и инфантам Don Antonio and Don Carlos, когда эти трое были Наполеоном помещены под домашний арест, превратившись в "гостей" великолепного замка, принадлежащего Maurice de Talleyrand Maurice de Talleyrand представил часовщика терецкому послу в Париже Morali Ali Effendi, который не только открыл Брегетту рынок Оттоманской империи, но и давал тому всевозможные ценные советы по турецкому рынку, до этого монополизированного англичанами. Все связи Брегетта делали возможным не только преодолевать трудное и опасное революционное время и быстро восстановить фирму при возвращении в Париж, но также охранять от других экономических катаклизмов, вызванных конфликтами в бушующей Еропе конца ХVIII начала XIX века. Опять таки, наполеоновские войны, Континентальная блокада изолировали Францию от остальной Европы и прекратили все коммерческие связи с Англией. Это в дополнение к экономическим трудностям в самой Франции и подтолкнули Брегетта искать другие точки сбыта свое продукции. His network of friends came to his aid yet again, in the form of a new market that opened up to him thanks to his friend General Hédouville [General comte de Gabriel-Marie-Joseph-Théodore Hédouville, comte d' (1755-1825), was envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to Russia from April 1802 to June 1804.], who in 1801 had become Plenipotentiary Minister in St. Petersburg [French ambassador]. A letter dated 17 Germinal year 11 (April 7, 1803) reveals the full importance of his role in introducing Breguet to the Russian market. Not only did the General praise Breguet’s skills to his entourage, he truly acted as a commercial agent. The letter makes reference to no fewer than five watches: a “souscription” watch, for which Breguet has received payment, a smaller watch with two hands that he intends to send within the month, two other “souscription” watches, one of which is to be sent to the Swiss Ambassador to Russia, and a gold engine-turned “souscription” watch for the price of 361/2 Louis that Breguet has given to another friend who is to deliver it to Hédouville so that he may sell it whenever possible. General Hédouville only remained in St. Petersburg until 1804, but it seems that during those few years, he was able to introduce Breguet to the most influential people at the Czar’s Court. Despite the fact that neither Abraham-Louis nor his son Antoine-Louis ever traveled to Russia, business developed quickly. Breguet entrusted watches to watchmakers in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Many others were sold through intermediaries such as Frackmann, Labensky, Hocke, Ferrier and Wenham. Business was so good that in 1808 Breguet decided to open a branch of his establishment in Russia. 2 He sent Lazare Moreau to run it, an ambitious young man who had had great success the previous year when he visited all the important European courts and all the Grand Army headquarters. On the way home, he had even stopped at Compiegne where he sold several watches to the king and queen of Spain as well as their Prime Minister, Manuel Godoy, Prince of Peace. Antoine-Louis Breguet, who was the firm’s bookkeeper, began a new account that he entitled "Maison de Russie". There he kept records of the production costs and sale prices of eighty pieces, “perpétuelle” watches, “souscription” watches, repeating and “à tact” watches, thermometer rings and silver pocket thermometers, various kinds of carriage clocks, which amounted to a total of nearly 90,000 francs at the time. All these goods were entrusted to Lazare Moreau, whose nickname was “Zarenne”. Moreau, whom Breguet had allowed to call himself "Monsieur Moreau-Breguet" for the occasion, left Paris in late spring. He arrived in Frankfort on August 25, was in Berlin on the 27th and by the 14th of September had arrived in Koenigsberg. There a friend of Breguet, Count Stalkberg, introduced him to the Grand Marshal of the Palace, who in turn introduced him to the Emperor, only a few days after his arrival in the city. Very optimistic, Moreau writes Breguet: "After having had lunch with him, we went to see His Majesty, who told me he was extremely pleased that a representative of the famous Breguet was setting up shop in the city, and that I could be sure of his protection and encouragement." Moreau sold the Czar a traveling clock and a gold and enamel “à tact” watch. He stated in his letter that the Czar wore only Breguet watches. On October 20 Moreau arrived in St. Petersburg. He had, however, spent a great deal of money to get there, for his carriage was so heavy that five to eight horses were required to pull it, and horses were rare due to the fact that most had already been reserved by important and wealthy travelers. In addition, the customs duties on the items he was carrying were extremely high. After having spent eight days at the “Hôtel de Londres”, Moreau rented an apartment at number 42 Avenue Grande Millione for 500 rubles per year. He bought furniture, rented a carriage, began going to all the receptions he could in order to meet people, and paid many social calls. He met the Minister of the Navy “who received me very cordially and promised to ask the Czar upon his return, which ought to be very soon, for permission to bear the title of Horloger de la Marine”. On November 12, 1808, that permission was granted and Moreau informs Breguet: "his Majesty accorded me an audience of an hour and a half, and told me that he had made me “Watchmaker to His Majesty and to the Imperial Navy”. Moreau took advantage of this audience to sell the Czar the “Pendule Sympathique” No. 423 (today in the Breguet Museum), with its assorted watch, as well as chronometer no. 2115). The sovereign granted Moreau permission to attend Court as often as he liked, saying “work for our Navy, Monsieur Moreau, and as soon as you have something new, be sure and show it to me”. Back in Paris, however, Breguet feels that Moreau is squandering money: a coachman, a servant, a horse, a carriage, a sleigh! He fears that Moreau is living far above his means, and accuses him of not accounting sufficiently for his expenditures and of only sending Breguet money after having received several reminders. Generally Moreau makes payments by means of bills of exchange, but once he sent diamonds, believing it was a good choice, but in fact the diamonds brought only a meager sum when sold in Paris. 3 On another occasion the rate of the ruble had dipped so low that Moreau’s efforts were practically for nothing. Finally, Breguet asked Augustin de Betancourt to keep an eye on Moreau.  Augustin de Betancourt was an old friend of Breguet’s, perhaps his oldest and best

friend. He had helped to develop the metal thermometers that Breguet made,

and had assisted Breguet in his improvements to the telegraph, which the

watchmaker had invented, along with Chappe, several years previously. Augustin de Betancourt was an old friend of Breguet’s, perhaps his oldest and best

friend. He had helped to develop the metal thermometers that Breguet made,

and had assisted Breguet in his improvements to the telegraph, which the

watchmaker had invented, along with Chappe, several years previously. While still in Spain, Augustin de Betancourt had been spared no effort on his friend’s behalf, introducing him at Court and selling many watches. While on a short journey to St. Petersburg in 1807, he had met the Czar, who had encouraged him to come to Russia in order to found a Corps of Hydraulic Engineers, promoting him to the rank of General. Augustin de Betancourt arrived in St. Petersburg on October 19 and met Moreau the next day. Moreau’s letters to Breguet show that the relationship between the two men remained cordial until 1809. They saw each other frequently and Moreau appeared to accept the advice dispensed to him by Monsieur Augustin de Betancourt Breguet, however, was growing more and more impatient over what he considered Moreau’s extravagant spending and negligence in business affairs. He even considered traveling to St. Petersburg to confer with Augustin de Betancourt over the best means of straightening out the affairs of his “Maison de Russie”. He eventually gave up the idea, but entrusted his friend with the delicate mission of relieving Moreau of his duties. The latter begged for a reprieve, saying that Breguet’s confidence was too precious for him not to wish to regain it; he was to partially succeed in this task. This explains why nearly 170 pieces, among them some of the most exceptional ever made by Breguet, were sold in Russia between 1808 and 1810. A watchmaker was specially dispatched to Russia, merely to assure the service and maintenance of these pieces. Unluckily for Breguet, relations between Napoleon and the Czar had considerably deteriorated, and in the spring of 1811 Moreau was obliged to flee Russia, with no time to pack up his furnishings or even his material. He entrusted Augustin de Betancourt with the task of collecting bills as yet unpaid. The closing of his “Maison de Russie” was very hard on Breguet, especially since he had already lost his outlets in Spain and England. Fortunately, he was able to retain the clientele of most of the Russian aristocrats. In all, over 270 pieces were sold in Russia, and the name “Breguet” was considered to be a synonym of “chronometer”. 4 The watchmaker’s fame was so great that his name appears several times in Russian literature. In 1825, Alexander Pushkin wrote, in his Eugene Onegin : “Meantime, he dons his morning coat A high hat places on his head. His horse the boulevard will tread, And freely range till Eugene note (Helped by his vigilant Breguet) That time has come for lunch today.” ---- Покамест в утреннем уборе, Надев широкий боливар, Онегин едет на бульвар И там гуляет на просторе, Пока недремлющий брегет Не прозвонит ему обед ---- Уж восемь робертов сыграли Герои виста; восемь раз Они места переменяли; И чай несут. Люблю я час Определять обедом, чаем И ужином. Мы время знаем В деревне без больших сует: Желудок - верный наш брегет ---- Еще бокалов жажда просит Залить горячий жир котлет, Но звон брегета им доносит, Что новый начался балет. 5 After the fall of Napoleon in 1814, Breguet’s commercial relations with Russia again flourished, with the assistance of enterprising agents, whose addresses are often mentioned on the certificates of the watches sold there. Breguet further states that the watches may be repaired and maintained: “In Moscow by Monsieur Ferrier In St. Petersburg, by Wenham, Perspective Nevski 66.” The ink was hardly dry on Napoleon’s act of abdication when on April 2, 1814, Czar Alexander 1er -- who was staying in Monsieur de Talleyrand’s Paris residence in the rue Saint-Florentin -- paid a personal call on Breguet and bought two watches. It was probably during this visit that he also placed an order for a series of “compteurs pour régler le pas des troupes” such as No. 3825, which was delivered for him to General Brosin (today in the Musée Breguet). Like their sovereign, most Russian aristocrats paid a visit to Breguet whenever they traveled to Paris, to place their orders in person. The watches were delivered through the Russian embassy in Paris. Count Charles André Pozzo di Borgo, a Corsican who had become the Russian ambassador in Paris, bought a very fine gold pocket chronometer on July 28, 1826 (today in the Musée Breguet). Breguet’s commercial relations with Russia continued, with both good periods and difficult ones, until the October Revolution of 1917 Источник 1812 |

|